Who in their right mind rolls out of bed at an unsociable hour on a Saturday morning and treks to rain drenched Newbridge to talk about work stuff on their day off?!

As it happens — quite a lot of people do. From far and wide (North Wales, Leeds and London!) people gathered to talk about the challenges and opportunities the housing sector (and their partners) are facing.

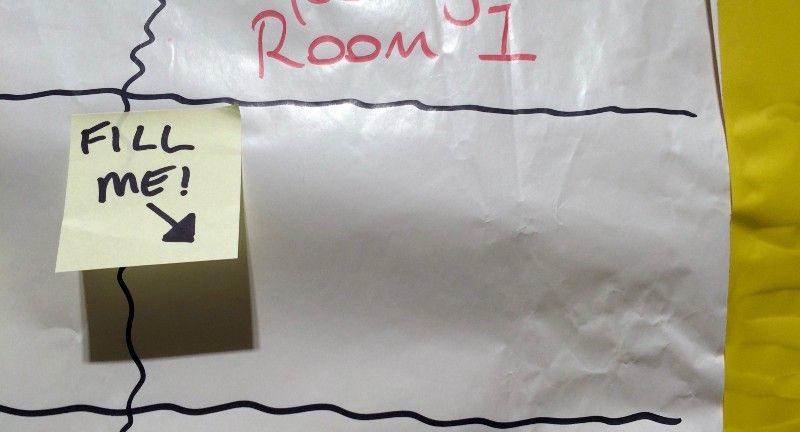

Unlike a traditional conference where a series of presenters give pre-defined talks on stage (and occasionally try to inflict death by powerpoint) an unconference has no set agenda and no set speakers. The attendees decide what’s going to be talked about during the day by standing up and pitching their ideas for discussions to the rest of the room. For a more in-depth explanation see this blog post about the format.

Before the finer points of the event started to dissipate in my brain, I wanted to scribble something down about each session I attended. These are by no means exhaustive minutes of everything that was spoken about, just personal highlights of the discussions I was sat in. If I’ve horribly misquoted or misattributed you — let me know and I’ll happily edit accordingly. 🙂

Session 1 — Breaking patterns & getting off the wheel

This session was pitched by Esko Reinikainen and was all about how to identify patterns in your work and how to avoid repeating them if they have a negative impact. For example — do you check your email each morning before you start work? Is that the most productive start to your day or does it send you into a zombified stupor by 11am? If you’re able to identify that checking email early is counterproductive — how would you change that pattern of behaviour for a more positive outcome? Perhaps you could only check email between certain pre-defined hours.

Everyone seemed to recognise the need to build ‘reflective time’ into work in order to understand what our patterns are. There was a general feeling that reflection isn’t treated as a priority. In order to do something differently, you need to put your creativity to work and think differently and that can be hard to do that amongst the barrage of telephone calls, email notifications and desk visits.

There was also some talk about the hierarchies that our organisations use and whether they enable set patterns. They are built for the industrial age, where work was complicated but predictable and best tackled by being broken down into defined areas of responsibility. The problem is that people increasingly need to work outside of the command & control structures to get stuff done. Work is becoming less predictable and more complexe. Every organisation has a second undocumented structure called the social network. This is defined by who works with who most often and most effectively. It can often span different departments and responsibilities and functions ‘bottom up’ rather than ‘top down’. These new networks hint at the way organisations could operate in the future, where people are clustered around a purpose rather than predefined roles or job titles.

We also talked a bit around the theme of how do you get a culture of trying new things. Often there’s a barrier against the new or unusual, particularly in the public and third sector where most things we do are publicly funded in one way or another and risk is actively avoided for fear of bad PR. We collectively pondered how we can start to build a culture of ‘giving things a go’ and being more honest about when stuff doesn’t work as expected. We touched upon the way that Bromford has chosen to embrace failure and actually promote it as a positive thing with a stated goal of trying to fail at least 70% of the concepts that come through the innovation lab.

Key takeaways for me from this session — Start small, test and reflect. Don’t fear failure, it’s all about the learning! And when enacting change it’s often easier to ask for forgiveness than it is to ask for permission, particularly when you have the best intentions at heart.

Session 2 — Innovation, what is it?

This was my own session that I pitched earlier in the morning. There’s been lots of talk about the urgent need for innovation for what seems like an eternity, but it’s a really ambiguous term that gets applied to lots of different stuff. I wanted to get an understanding of what innovation actually looks like as a day to day activity for an organisation.

We started by defining what innovation actually is. Esko defined it as “the successful embodiment of a useful idea into the marketplace”. And as he succinctly put it “anything else is just daydreaming or vanity projects”.

We went on to talk about what that actually means in practice. Esko drew up a basic innovation framework they use at the SatoriLab on the wall. It’s essentially split into 3 parts.

- Problem phase

- Ideation phase

- Solution phase

The problem phase is where you identify the thing that you’re trying to fix. It’s critical that you get this phase right or everything that follows it will be misguided. You have to fully understand the nature of the problem before you attempt to generate ideas to fix it. People have a tendency to be drawn to problems which they can already see a potential solution for — this urge should be resisted! Sometimes the most innovative ideas don’t have a clear outcome at the beginning.

The ideation phase is where you generate lots of ideas to fix the problem. Ideas should be treated ‘cheaply’. We need to generate lots and lots of them and cast the useless ones away rapidly. It was recognised that people who come up with ideas often cling on to them as being precious. We need to encourage a culture of failure — although it was thought failure is a bit of a loaded term for some. I liked the suggested re-brand of being ‘unsuccessfully successful’. In the ideation phase you’ll create a prototype and begin testing. The ideation phase might revert back into the problem phase if it looks like the original framing wasn’t quite right. The process can be iterative.

Next is the solutions phase. This is where you’ll design and pilot your chosen idea to make sure its viable and scalable. You’ll continue to work with potential users of the service or product to make sure it’s actually fixing the problem you identified. If everything goes according to plan, you release it as live for full implementation.

During the session I shared some of the innovation practices we’d tried within my own organisation which had been met with mixed success. What became evident is that innovation can’t be confined to a select club, group, department or location. To make the biggest impact we need to identify the key problems the organisation is facing and bring the right mix of people to together to find a solution for them — for starters, those with the most intimate knowledge of the problem.

The key take away for me from this session is that the process itself really doesn’t have to be rocket science. By clearly identifying a problem to fix at the start, it’s easier to rally people around a common cause and keep them engaged in the process. This is in contrast to it becoming this indistinct thing which is detached from the day to day operation of the organisation. In essence this is how you make it relatable so that anyone can join in and play a part innovating. To support this you need to foster the right cultural conditions for transparency and learning.

Session 3 — User centered design for housing services

This session was run by Jo Carter. The pitch was centered around her recent experience of applying user centered design for Monmouthshire Housing Association.

The process broadly went as follows..

- Interviewed a random selection of tenants in their homes

- Questions were open and non leading

- Very informal chat, encouraged tenant to generally talk about themselves

- Asked things like how they pay rent, where they keep their documents etc.

- From the interviews they created ‘personas’ for different types of tenants

- Staff ran through the customer journey from the viewpoint of the different personas, to see what people would think or feel in different touch points with the organisation.

- Staff ran through the customer journey from the viewpoint of the different personas, to see what people would think or feel at different touch points with the organisation.

Having done this, Monmouthshire HA were able to gain an even greater understanding of the range of customers that use their services and tweak things accordingly to suit their differing needs (for example : up-skilling customer services to deal with a broader range of calls, redeveloping the website to make it more tenant focused).

The end of the session diverged slightly into a talk about whether it’s possible to do user centered design with closed proprietary housing systems. Any changes would require development cost and consultancy (therefore harder to tweak and iterate with a price tag attached). Would an open source alternative give us greater control to shape our services? Is IT generally seen as a barrier to getting this stuff done?

We then started to talk about the viability of having an open source housing system — something that every social housing organisation could contribute toward via a repository like github and use/modify freely. One camper voiced concern about openly sharing their code as the development had cost the association time and money — surely they should get fair compensation for their intellectual property?

Unfortunately at that point, the session ended — but I look forward to picking this up again soon! I feel like there’s huge potential to be explored around open source frameworks for public services — particularly when driven by user centered design.

Key take aways for me — we should be designing services by observing what people need, not presuming what they want. I think perhaps we do some of that intuitively already — but we definitely need to be more explicit about getting outside of our four walls and speaking to people about services for greater insight into what’s working well and not so well.

Reflection on Housing Camp Cymru

There’s definitely something about the unconference format that creates a completely different feel from your usual conference day. Perhaps it’s because people are volunteering their own time rather than attending in an official ‘work’ capacity. The high level of participation was really impressive — none of those tumble weed moments when people ask questions and it’s met awkward with silence.

It’ll be really interesting to see what effect Housing Camp Cymru has a few months on and how the collective buzz converts into direct action. Until the next one comes around, I’ll be looking for my next unconference fix at every available opportunity. Be that Housing Camp, Housing Camp North West, UK Gov Camp, Gov Camp Cymru or Bara Brith Camp!

I’ll leave you with some other campers thoughts of the day.